How the Death of JFK’s Son Ignited Interest in ECMO

A little over a half-century ago, the nation was transfixed by a struggle to save the life of Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, the infant son of President John F. and Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. Patrick, 5½ weeks premature and weighing only 4 pounds 10½ ounces, was delivered on Aug. 7, 1963. After birth, he immediately began having trouble breathing and was transferred from Cape Cod to Boston Children’s Hospital where he was placed in a hyperbaric chamber. He died 39 hours later of hyaline membrane disease, which was then the most common cause of death among premature infants (25,000 per year) in the United States.1 The disease is now known as infant respiratory distress syndrome (IRDS). In those days, there were no neonatal intensive care units (NICU), and ventilators had yet to be used for premature babies.

The morning after his death, Patrick’s obituary in The New York Times pointed out that, at that time, all that could be done “for a victim of hyaline membrane disease is to monitor the infant’s blood chemistry and to try to keep it near normal levels. Thus, the battle for the Kennedy baby was lost only because medical science has not yet advanced far enough to accomplish as quickly as necessary what the body can do by itself in its own time.”

The tragic death of the president’s son sparked interest in research on prematurity and, over the following decades, innovations from physicians, nurses and others led to bold and successful treatments for infants. This gave rise to a new specialty, neonatology and the establishment of neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) around the country. Had Patrick been born today, his outcome most likely would have been positive due to the groundbreaking work of neonatology pioneers such as Dr. Robert Bartlett of the University of Michigan who developed extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) to treat IRDS.

ECMO Pioneer Dr. Robert H. Bartlett

Fifty years ago, there were few treatment options for infants, children or adults with severe respiratory disease syndrome. Due to the herculean and innovative efforts of pioneers such as Dr. Robert H. Bartlett, professor emeritus from the University of Michigan, treatment by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation also came into being and has continued to evolve. It remains a last ditch effort to treat neonatal, pediatric and adult patients who are suffering from severe respiratory syndrome and/or cardiac failure who are not responding to other medical treatments. But ECMO has reduced infant mortality from 80% to 25% for critically ill infants with acute reversible respiratory and cardiac failure from conditions such as persistent pulmonary hypertension, meconium aspiration, and sepsis who are unresponsive to conventional therapy.

Flow Pioneer Transonic

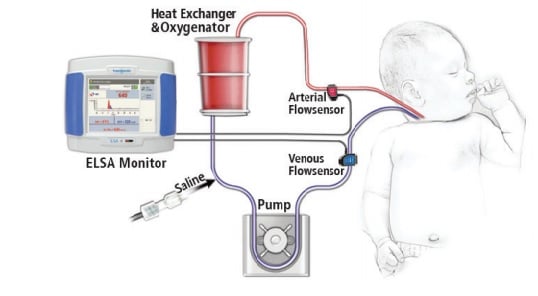

Hand in hand with the evolution of ECMO has been Transonic‘s development of Flowsensors that can clamp-on sterile tubing and measure the volume flow inside the tubing. The first Transonic Tubing Flowsensors were introduced in 1987. Incremental improvements in the sensors, which now have a 4 “X-style” crystal configuration, has expanded their measurement capability in tubing circuits. XL-Flowsensors can now accurately measure with minimal zero offset the 300-500 mL/min low flows found in ECMO circuitry.

Reference: 1 NY Times JULY 29, 2013, Lawrence K Altman, M.D.