Henrietta Lacks and the Evolution of Informed Consent

When any of us go to a doctor’s office or hospital for even a minor procedure, we are immediately handed paperwork. Among the papers that must be signed invariably is one that provides “informed consent” for having the procedure or treatment. Informed consent is a process for getting permission before conducting a healthcare intervention. A healthcare provider must ask a patient to consent to receive therapy before providing it, or a clinical researcher must ask a research participant before enrolling that person into a clinical trial.

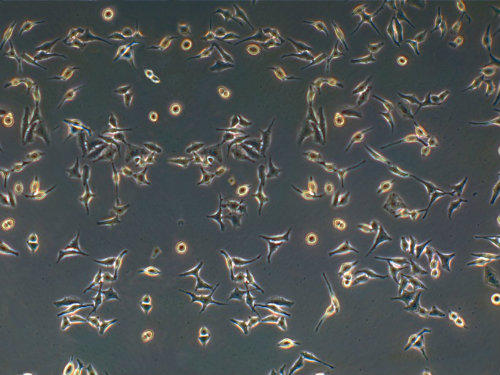

HeLa

This was not always the case. Up into the early 1970s, patients in the United States would have procedures performed and even be subjects of research experiments without their consent. One egregious example of this was the case of Henrietta Lacks, chronicled in the 2010 New York Times bestseller by Rebecca Skloot, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Henrietta Lacks was an African-American woman who became the unwitting source of cells cloned for culture.

On Jan. 29, 1951, shortly after the birth of her son Joseph, Lacks entered Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore with profuse bleeding. She was diagnosed with cervical cancer and was treated with inserts of radium tubes. During her radiation treatments for the tumor, two samples—one of healthy cells, the other of malignant cells—were removed from her cervix without her permission. Later that year, 31-year-old Henrietta Lacks succumbed to the cancer.

The cells were given to Dr. George Gey who had been attempting to culture human cells for years. But Lacks' cells were different. He was able to isolate one specific cell from Lacks, multiply it, and start a cell line that he named HeLa, using Henrietta Lacks' initials. These first “immortal” lab-grown human cells soon became the culture used in numerous experiments. In 1954, the HeLa strain was used by Jonas Salk in his development of a polio vaccine. In 1955, the HeLa cells were the first human cells successfully cloned for mass production and now more than 20 tons of Lacks’ cells have been grown. There are almost 11,000 patents involving HeLa cells.

One person to use HeLa cells to experiment on human subjects, without their “informed” consent, was Dr. Chester Southam, head of virology at Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research in New York City. In 1954, he began to inject HeLa cells into patients already diagnosed with cancer to see if their immune systems would accept or reject the new cancer cells. When tumors grew, he removed them. Then, Dr. Southam wanted to see how a control group of healthy patients would also react to the injections. He sought volunteers from an Ohio penitentiary and began injecting prisoners whose healthy immune systems did ward off the cancer. In subsequent years, Southam injected cancer cells into more than 600 people without telling them. But, in 1963, when he asked doctors at the Brooklyn Hospital for Jewish Chronic Diseases to inject their patients with the cells, they balked. They knew, only too well, of Nazi research on Jewish prisoners and the 10-point Nuremberg Code of ethics that evolved from the Nuremburg trials in 1947. The code states up front in its first line, “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.”

Declaration of Helsinki

Ironically, although the American Medical Association had created rules protecting laboratory animals in 1910, no comparable recommendations for human research and requirements for informed consent existed until the Nuremberg Codes. In 1964, the Declaration of Helsinki codified regulations for international research involving human subjects. Regarded as the ethical cornerstone for human research, some of its guidelines included the principles that “research protocols should be reviewed by an independent committee prior to initiation" (an Internal Review Board or IRB) and that “research with humans should be based on results from laboratory animals and experimentation.” Also, “informed consent” became a right for any human subject participating in any clinical research.

References: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot, 2010 Crown Publishing House, New York, NY